By Tony Collins

Front page of a report the DWP kept hidden for four years. The DWP’s lawyers went through numerous FOI appeals to try and stop the report being published.

This is the independent Universal Credit Project Assessment Review that lawyers for the Department for Work and Pensions went through numerous FOI tribunal appeals trying to keep hidden.

It was written for the DWP by the Cabinet Office’s Major Projects Authority. Interviewees included Iain Duncan Smith and Lord Freud who was – and is – a work and pensions minister.

In 2012 Lord Freud signed off the DWP’s recommendation that an FOI request for the report’s release be refused.

Remarkable

The now-released report is remarkable for its professionalism and neutrality. It’s also remarkably ordinary given the number of words that have been crafted by the DWP’s lawyers to FOI tribunals and appeals in an effort to keep the report from being published.

The DWP’s main reason for concealing the report – and others that IT projects professional John Slater had requested under FOI in 2012 – was that publication could discourage civil servants from speaking candidly about project problems and risks, fearing negative publicity for the programme.

In the end the DWP released the report 11 days ago. This was probably because the new work and pensions secretary Stephen Crabb refused to agree the costs of a further appeal. Last month an FOI tribunal ordered that the project assessment review, risk register and issues register be published.

Had the reports been published at the time of the FOI request in 2012 it might have restricted what ministers and the DWP’s press office were able to say publicly about the success so far of the Universal Credit programme.

In the absence of their publication, the DWP issued repeated statements that dismissed criticisms of its programme management. Ministers and DWP officials were able to say to journalists and MPs that the Universal Credit programme was progressing to time and to budget.

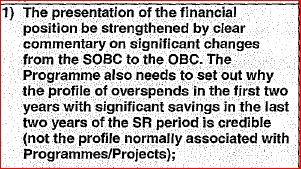

In fact the project assessment review questioned a projected increase of £25m of IT spend in the budget.

MPRG is the Major Projects Review Group, part of the Cabinet Office. OBC is the Outline Business Case for Universal Credit. SOBC is the Strategic Outline Business Case.

The DWP claimed in the report that the projected of £25m in IT spend was a “profiling”rather than budgetary issue.

By this the DWP meant that it planned to boost significantly the projected savings in later years of the project. Those anticipated savings would have offset the extra IT spend in the early years. Hence the projected overspend was a “profiling” issue.

But the report questioned the credibility of the profiling exercise.

On the question of whether the whole programme could be afforded the report had mixed views.

The report was largely positive about the DWP’s work on Universal Credit. It also revealed that in some ways not all was progressing as well as had been hoped (which was contrary to DWP statements at the time). The report said,

And a further mention of “behind the curve”…

None of these problems was even hinted at in official DWP statements in 2012. About six months after the project assessment review was conducted, this was a statement by a DWP minister (who uses words that were probably drafted by civil servants).

“The development of Universal Credit is progressing extremely well. By next April we will be ready to test the end to end service and use the feedback we get from claimants to make final improvements before the national launch.

“This will ensure that we have a robust and reliable new service for people to make a claim when Universal Credit goes live nationally in October 2013.”

And the following is a statement by the then DWP secretary of state Iain Duncan Smith in November 2011, which was around the time the project assessment review was carried out. Doubtless his comments were based on briefings he received from officials.

“The [Universal Credit] programme is on track and on time for implementing from 2013.

“We are already testing out the process on single and couple claimants, with stage one and two now complete. Stage 3 is starting ahead of time – to see how it works for families.

“And today we have set out our migration plans which will see nearly twelve million working age benefit claimants migrate onto the new benefits system by 2017.”

Ironic

It’s ironic that the DWP spent four years concealing a report that could have drawn attention to the need for better communications.

The report highlighted the need for three types of communication, internal, external and with stakeholders.

On communications with local authorities ..

Comment

The DWP has denigrated the released documents. A spokesperson described them as “nearly four years old and out of date”.

It’s true the reports are nearly four years old. They are not out of date.

They could hardly be more important if they highlight a fundamental democratic flaw, a flaw that allows Whitehall officials and ministers to make positive public statements about a huge government project while hiding reports that could contradict those statements or could put their comments into an enlightening context.

Stephen Crabb, IDS’s replacement at the DWP, is said by the Sunday Times to want officials to come clean to him and the public about problems on the Universal Credit programme.

To do that his officials will have to set themselves against a culture of secrecy that dates back decades. Though not as far as the early 1940s.

Official proceedings of parliament show how remarkably open were statements made to the House during WW2. It’s odd that Churchill, when the country’s future was in doubt, was far more open with Parliament about problems with the war effort than the DWP has ever been with MPs over the problems on Universal Credit.

I have said it before but it’s time for Whitehall departments, particularly the DWP, to publish routinely and contemporaneously their project assessment reviews, issues registers and risk registers.

Perhaps then the public, media and MPs will be better able to trust official statements on the current state of multi-billion pound IT-based programmes; and a glaring democratic deficit would be eliminated.

Openness may even help to improve the government’s record on managing IT.

Universal Credit Project Assessment Review

Is DWP’s Universal Credit FOI case a scandalous waste of money?