By Tony Collins

“To my shame I didn’t know very much about this,” said actor Toby Jones. He was speaking at a press screening at BAFTA of “Mr Bates v The Post Office“, a star-studded ITV drama series on the Post Office IT scandal.

The series has prime-time TV slots: the first 60-minute episode will air on New Year’s Day at 9pm on ITV and ITVX, followed by three further episodes on consecutive evenings at 9pm.

Some scenes in the episodes may lodge in the national psyche, in a way that news stories on the scandal rarely have, however influential they were at the time.

Also being aired in the first week of January is an ITV documentary on the scandal Mr Bates vs the Post Office: The Real Story. It will go out on the same evening as the final episode, 4 January, at 10.45pm.

The series has a a focus on how a respected state-owned institution, the Post Office, intervened in the normal family life of branch sub-postmasters, sub-mistresses and their staff, in ways that had lasting effects on young children, grandparents, wives, husbands and partners.

People watching may need to remind themselves that the story is based on fact not fiction.

“You can’t believe it’s true,” said cast member Will Mellor who plays former sub-postmaster Lee Castleton. “Even when we were filming it, I just kept saying ‘I can’t believe they’ve actually done this to these people.’”

At one level it’s a mystery story. Why did the Post Office’s corporate executives and others at a senior level, including auditors, investigators and lawyers, seem to try and outdo each other in demonstrating inhumanity towards sub-postmasters and their families?

The context

Toby Jones plays Alan Bates, the former sub-postmaster who, with help from forensic accountant Kay Linnell and solicitor James Hartley, raised the tens of millions of pounds needed to sue the Post Office and expose the widest miscarriage of justice in British legal history.

The Bates-led litigation proved that Fujitsu’s Horizon system, as rolled out to thousands of local Post Office branches, was faulty and the cause of mysterious shortfalls in sub-postmaster accounts.

The system not only had bugs, defects and errors but Fujitsu staff working at a central location had “remote access” to Horizon systems as used by sub-postmasters in their local branches.

This remote access meant Fujitsu staff could alter financial balances of branch accounts systems – without the knowledge of sub-postmasters.

The Post Office did not want anyone outside the corporate Post Office to know about remote access or Horizon’s bugs, errors and defects.

It was easy to keep these things hidden because of a culture of impunity: the Post Office remains a commmercial enterprise that cannot go bust or be held properly to account because it is 100%-owned by government.

Within this no-consequence culture, the Post Office was able to maintain a pretence that Horizon was robust.

Had the pretence been left at that, a mere pretence, nobody would have much noticed or cared. But the Post Office took the pretence many stages further: it prosecuted more than 700 postal workers on the back of Horizon’s unreliable data.

Former postal workers went to prison for theft when the Post Office knew they hadn’t stolen anything. The Post Office also forced some into bankruptcy and confiscated their homes. Sub-postmasters parted with personal possessions such as wedding and engagement rings to pay phantom debts. The Post Office removed sub-postmasters’ livelihoods rather than own up to Horizon’s faults. Postal workers were pressured to confess they had stolen money when they knew they had stolen nothing: they hoped their made-up confessions would keep them out of jail – but some still went to jail anyway. Marriages broke up. Many sub-postmasters suffered health problems. More than 60 died without compensation. Some committed suicide.

Some also gave in to Post Office pressure, in plea bargaining, not to criticise Horizon in their court cases or defence statements.

It is only since the Bates v Post Office litigation ended in 2019 that the general public has begun to learn of the scandal. Before that, some national newspapers were wary about reporting the scandal for legal reasons but Bates’ success in the litigation proved without doubt the existence of remote access and errors, bugs and defects in the system.

Since then, several national newspapers have had the legal confidence to bring the scandal to public attention. Ten years before, in 2009, Rebecca Thomson of Computer Weekly broke the story of the scandal and the magazine’s Karl Flinders has maintained the magazine’s reputation for revelatory pieces. Journalist Nick Wallis has also kept the scandal in the public eye with his blog, TV and radio documentaries and his book “The Great Post Office Scandal“. Private Eye and more recently The Law Society Gazette have also given the story important coverage, as has Tom Witherow of the Daily Mail and then The Times.

The ITV series will take media coverage of the scandal further: at prime-time for much of the first week in January, millions of TV viewers will see a sharp contrast between some of those who worked for the corporate Post Office, who seemed to live in a fantasy world where Horizon could do no wrong, and the branch sub-postmasters and their families who became victims of that Post Office fantasy.

Writer Gwyneth Hughes has not shied away from the technology. Remote access is shown in a scene involving former sub-postmaster Michael Rudkin, played by Shaun Dooley.

In his official capacity as a negotiator on behalf of sub-postmasters, Rudkin visited Fujitsu’s offices in Bracknell to discuss problems with the Horizon system. When he recognised Horizon terminals in a computer room he visited and asked an operator if he was working on live Horizon data, the operator said he could alter a bureau de change figure to show that the data was live. The operator then laughed and said, ‘I’ll have to put it back. Otherwise, the sub-postmaster’s account will be short tonight.”

Rudkin expressed concern, because he had been told that remote access wasn’t possible. At that point, Rudkin was politely but speedily taken to Fujitsu’s reception, and he was told to leave the building.

The next day, the Post Office claimed that Rudkin’s branch had a £44,000 loss. Rudkin’s wife Susan was subsequently charged with false accounting and given a wrongful criminal conviction. The Post Office meanwhile applied for a confiscation order on all his property and he had his bank account frozen under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. He also lost his job.

The destruction of the Rudkins’ lives features in the ITV drama. What may linger in the mind, however, was the Post Office’s denial that Rudkin had visited Fujitsu. Rudkin was able to prove otherwise, which leaves the viewer to wonder whether the Post Office cares much about the truth – or indeed whether it has any need to care about the truth.

Susan Rudkin’s conviction was overturned in 2020. The couple recently described the Post Office’s compensation offer as “obscene”.

Why the reach of ITV Post Office drama series is important

Speaking between screenings of the drama’s various episodes, Toby Jones said he had understood little of the scandal before he came to be involved in the drama.

He said,

“Frequently it is quite hard to understand beyond the headline … there’s something by definition about sub-postmasters and sub-postmistresses that is unshowy, unflashy citizenry and when that comes onto the news there is a part of your brain that switches off … to my shame I didn’t know enough about it.”

Jones was abroad when he first called Alan Bates. “I said that I am the guy who is going to play you”, to which Bates jokingly replied, “Well you’re going to have a bit of a problem because I don’t have any emotion.”

Jones said,

“That did strike me as a bit of a problem … He claimed to have no emotional life … It becomes clear the toll it [the scandal] has taken on Alan and it is a great great tribute to his character, his doggedness, his determination and his sheer intelligence that the next person I rang was James [now Lord] Arbuthbnot, and asked whether it was a pain in the neck, ever, that Alan was phoning you to hassle you over this thing that was emerging …he said every time Alan Bates comes into my life it’s a privilege to be with someone who is fundamentally a good man.”

Jones added, almost smiling, “It’s hard to play a good man the kind of man I am.”

Several of the cast said they knew little of the scandal beforehand. That the parts they play may linger in the mind is a tribute to the skills of the actors and Gwyneth Hughes’ beautifully-crafted but hard-hitting script.

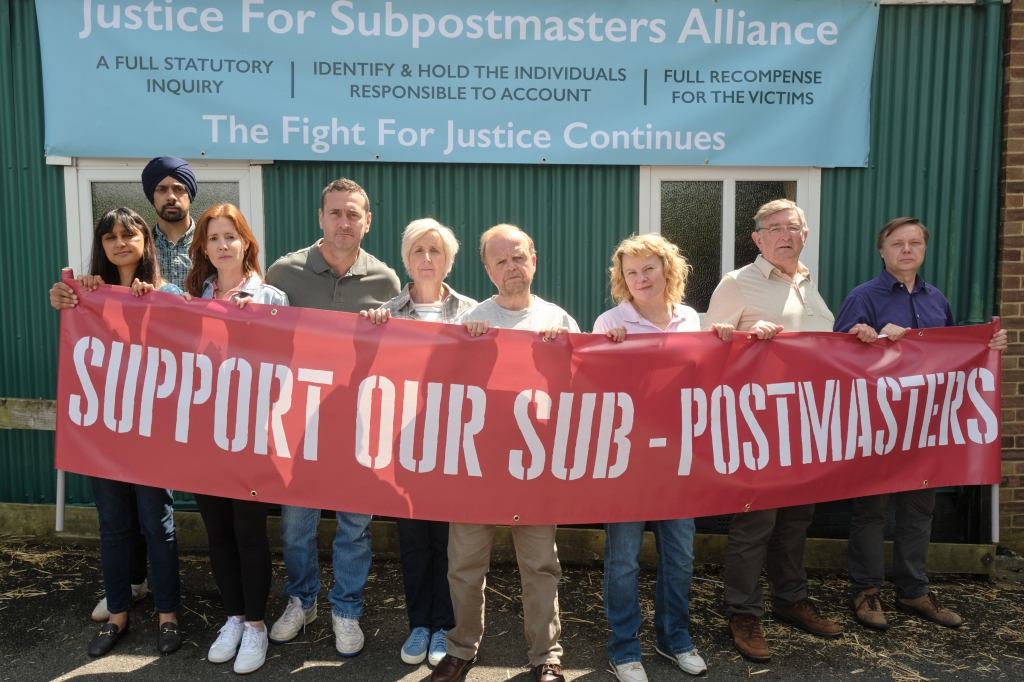

Hughes met and became a friend of some of the former sub-postmasters and sub-postmistresses as part of her research. The series focuses on Alan Bates and his partner Suzanne Sercombe (played by ex-Coronation Street actress Julie Hesmondhalgh). Former sub-postmistress Jo Hamilton (played by Monica Dolan) also has an important role in the series, as do Lee Castleton, James Arbuthnot (played by Alex Jennings) Noel Thomas (played by Ifan Huw Dafydd) and Pam Stubbs (Lesley Nicol).

Computer Weekly, whose reporter Rebecca Thomson investigated and wrote the first story on the scandal, also has a role in the drama.

Distressing

Hughes’ lightness of touch leavens otherwise distressing family stories. Below are some of the punchier lines of actors who play former postal workers. They are taken from some of the drama’s early episodes …

– “I wonder if they [the Post Office] know they’re talking bollocks.”

– “We’ll just trust in the British justice system and we’ll be alright.” [This is an innocent former sub-postmaster’s comment to his family in advance of his court hearings that have a grim conclusion]

– “They’re a bunch of lying bastards.” [A reference to the Post Office.]

“They have blood on their hands now.” [Alan Bates’ comment on learning that an innocent former sub-postmaster Martin Griffiths has stepped into the path of an oncoming bus. The drama shows Griffiths’ family life before his suicide.]

Tears

During a break in the screenings, several people in the audience spoke of wiping away tears. The audience comprised journalists, actors (including Jones) and some of the sub-postmasters whose lives were depicted in the series. One audience member who knew almost nothing of the scandal before the screening said she was enraged at the lack of accountability.

Cast members also commented on the lack of accountability. One said,

“The whole thing really is about accountability and power. Where is the accountability?”

Other cast members spoke of the scandal in the present tense. None saw it as resolved or purely in the past. One member of the production team spoke of …

“this hideous, ongoing miscarriage of justice.”

[Indeed, Wallis wrote last month of a sub-postmistress Teju Adedayo whose conviction has been overturned but the Post Office is refusing to pay her compensation.]

Mystery?

The Post Office’s motivations in protecting its brand above any humanitarian considerations mystified several of the cast. These are some comments of cast members,

– “People are going out of their way to make it impossible to resolve this”

– “They [the Post Office] are spinning it out [a reference to delays in paying compensation to victims]. I don’t know why. It is madness. What is motivating this blockage?”

– “It is very curious and it remains curious however much you read about it … I talk to Alan [Bates] about it. Why are they doing this? What makes people feel more loyalty to a brand than they do to victims who are dying? It is mysterious…. It is absolutely extraordinary that someone will lie in court to protect a brand. I cannot get my head around that.”

Comment

Mr Bates v The Post Office is likely to move the hardest of hearts.

It’s unconscionable for a state-owned instiutution to ruin one life. But the ITV drama goes into the ruined lives of family after family. Victims include children. Millie-Jo Castleton was eight when her father’s endless ordeals began. She is now 26 and still the after-effects continue.

Even today it’s difficult to tell whether most current and former Post Office officials, other than the chief executive Nick Read, have any lasting concerns over the IT scandal.

This year’s Bonusgate scandal, perhaps, captures the general corporate mood. It has emerged that dozens of Post Office executives have gained financially from the existence of a public inquiry into the scandal: the executives received bonuses for engaging positively with the inquiry.

One would have thought they’d have engaged positively without any special payment.

There’s no doubt Nick Read is sincere and earnest in his apologies for the scandal but most other executives, past and present, have yet to express shame and embarrassment at the corporate concealment of Horizon’s bugs, errors, defects and and the hiding of remote access, early exposure of which could have undermined hundreds of prosecution cases.

The four-hour ITV drama series, however, may hit the corporate Post Office in its most vulnerable spot: its reputation as seen by millions of ordinary people

The Post Office uses brand surveys to check how it is perceived by the man and woman in the street and, apart from occasional wobbles during a prolonged spell of bad publicity, its reputation holds up surprisingly well. The general public, perhaps, judge the Post Office on genial local sub-postmasters. The public might not care much about corporate attitudes and shennanigans.

The ITV drama may change that: it shows that sub-postmasters and the corporate Post Office are not the same thing.

Perhaps it’s little wonder the Post Office did not engage with the ITV series. Indeed, the various episodes may do little or nothing to make it easier for the Post Office to recruit at an executive level, which it is having trouble doing already: how many talented job-hunting executives would want “Post Office Head Office” on their CV?

But the drama has its positives: it may discourage the Post Office from continued unnecessary and apparently vindictive actions against some former sub-postmasters, alive and dead.

One case in point is the Post Office’s decision to spend public money this year opposing the posthumous appeal of Joanne O’Donnell. The Post Office is also refusing to pay compensation to some of those whose convictions have been overturned.

When compensation is paid, it is unusually inadequate and sometimes insulting. Today, nearly 24 years on from the start of the scandal, some victims are on the verge of destitution and are being threatened with eviction; they face being homeless because they cannot pay their rent. Others are dying without receiving full and fair compensation.

If nothing else, one hopes the drama will instill in current and former Post Office executives, lawyers, auditors, investigators and managers a sense of shame and embarrassment.

It’s just a suggestion but Sir Wyn Williams’ inquiry ought to have a new phase of hearings where his legal team questions successive generations of Post Office board executives who knew of Horizon’s faults but kept quiet and the Whitehall officials whose staunch resistance to effective checks and balances allowed the scandal to happen.

How did the scandal happen?

If you give a state-owned institution almost complete autonomy, a culture of impunity, an ability to operate in almost total secrecy, financial incentives that reward corporate loyalty and commercial performance rather than constructive criticism or challenge, and you top it all with a criminal justice system that encourages abuses of process when it comes to complex technology-based prosecutions, and you have the seeds of the Post Office IT scandal.

Government officials let an unaccountable organisation, the Post Office, buy a defective accounting system for its 18,000 retail branches, let it pretend the technology was robust when it knew it wasn’t, let it lie when challenged by IT experts and outsiders and let it plug any suspected financial holes shown on the system by making franchisees, sub-postmasters, cover discrepancies from their own pockets. The technological pretence was made all the more real when sub-postmasters were imprisoned, bankrupted and their livelihoods removed.

Officials also let it pay bonuses based on the organisation’s performance and, in some cases, bonuses for financial recoveries in the wake of successful prosecutions.

It would all have carried on like this had Alan Bates and his legal team not sued the Post Office. The High Court was the one thing the Post Office could not control – though it tried, by seeking the judge’s removal.

Thanks to Alan Bates there is now have the promise of justice for hundreds of former postal workers; and thanks to the ITV drama, millions of people will understand how brutal state officials and their lawyers can be when they cannot be held to account.

Also thanks to the drama, the general public will follow the lives of ordinary, and yet extraordinary, sub-postmasters, sub-mistresses and postal workers who worked hard to serve their local communities until the Post Office removed their livelihoods.

That the sub-postmasters had the misfortune to work for a state institution that treated them as thieving crooks says a great deal about the twin dysfunctions of a Whitehall machine that has no effective checks and balances and a criminal justice system that almost welcomes injustices in complex technology cases.

Meanwhile, what are we left with?

Perhaps a Post Office that is destined to spend the rest of his existence in the public sector making enemies, all watched on by an extraordinarly complacent government and criminal justice system.

That said, the scandal could provide an opportunity for real and genuine (not cosmetic) change in the government and criminal justice system. If this opportunity is lost, the scandal’s lesson-learning exercises will amount to nothing.

Mr Bates v The Post Office – YouTube trailer